EPISODE INTRO

In the 14th episode of the Japan Distilled podcast, your hosts Christopher Pellegrini and Stephen Lyman take a deep dive into sweet potato shochu. This continues a multi-part series breaking down the various subcategories of honkaku shochu, which are classified by ingredient type in the main fermentation.

CREDITS

Theme Song: Begin Anywhere by Tomoko Miyata (http://tomokomiyata.net/)

Mixing and Editing: Rich Pav (https://www.uncannyjapan.com/)

HOSTS

CHRISTOPHER PELLEGRINI Vermont born and bred, long-time Tokyo resident and author of The Shochu Handbook, Christopher learned about delicious fermentations as a beer brewer at Otter Creek (Middlebury, VT). He now spends most of his waking hours convincing strangers that shochu and awamori are unlike anything they’ve ever tried before.

STEPHEN LYMAN discovered Japan’s indigenous spirits at an izakaya in New York City. He was so enthralled that he now lives in Japan and works in a tiny craft shochu distillery every autumn. His first book, The Complete Guide to Japanese Drinks, was nominated for a 2020 James Beard Award.

Stephen and Christopher are both enormous sweet potato shochu fans and probably drink more of it than all other styles combined.

If you have any comments or questions about this episode of Japan Distilled, please reach out to Stephen or Christopher via Twitter. We would love to hear from you.

LINKS

Maya Aley’s excellent summary of sweet potatoes in Japan.

SHOW NOTES

Sweet Potato Shochu Origins

Sweet potatoes are not native to Japan. They aren’t even native to Asia. In fact, they were brought to Asia by Portuguese traders who sold them to the Chinese, who sold them to the Ryukyu Kingdom (Okinawa), who sold them to Riemon Maeda, a Japanese fisherman, who brought the spuds back to his home in the Satsuma Domain in 1703.

It is no surprise that the name of the fisherman who brought sweet potatoes to Japan is remembered more than 300 years later when virtually all other Japanese commoners of the time are completely lost to history. In 1732, a massive grain crop failure resulted in mass starvation throughout Kyushu. But not in Satsuma. There, the lives of thousands of citizens were saved thanks to the abundant sweet potatoes that grew very well in the rocky, volcanic ash-laden soil. Riemon Maeda was given credit.

Japanese Sweet Potatoes

In most American supermarkets, you might find 1 or 2 varieties of sweet potatoes for sale. At Whole Foods, there might even be 3 or 4. In Japan, there are over 500 varieties of sweet potato cultivated, and more than 50 of those are used for shochu production in southern Kyushu. Rice doesn’t grow very well south of the Hitoyoshi Basin, which we described in the rice shochu episode. Therefore, plenty of farmland in Southern Kyushu (or Minami Kyushu as the region is known in Japanese) is devoted to sweet potatoes.

Harvest occurs in the late summer to early winter, depending on the variety. Distilleries usually begin production in August or early September (smaller distilleries have a hard time sourcing early harvest potatoes, so they tend to start later) and are usually winding down in December or January unless they are aging the potatoes before distillation, in which case production can continue through early spring. A few of the largest distilleries have developed methods for freezing steamed sweet potatoes, which allows them to distill all year long.

The most common sweet potato used in shochu production is kogane sengan. These large, white-fleshed potatoes have been cultivated specifically for shochu. They are not usually consumed but are favored for shochu production due to their high crop yield per acre, high starch content (more alcohol potential), and the aromas and flavors they impart to the spirit.

Purple, red, and orange sweet potatoes, which are much closer to the sweet potatoes Americans can expect to find in their grocery stores, are used to make more premium sweet potato shochu since these are considered food items so prices are higher due to market competition. These are often referred to as satsuma imo (imo being the Japanese word for potato) throughout Japan. For many Japanese, the smell of a roasted satsuma imo evokes childhood memories of the pushcart salesman walking through their neighborhood sing-songing “yakiimo” over and over again (yaki being the Japanese word for grilled as is used in yakitori [grilled chicken] or yakiniku [grilled meat]).

Murasaki imo, or purple potatoes are often called Okinawa Imo as they are most often associated with Okinawan cuisine, but they are used in shochu production as well.

Sweet Potato Shochu

As with barley shochu, sweet potato shochu can begin with a rice koji or barley koji fermentation, but they are also occasionally made with sweet potato koji. By production volume, a vast majority of sweet potato shochu begins life as a rice koji fermentation. We would hazard to guess that this represents more than 99% of the market, though both Japanese short-grain rice or Southeast Asian style long-grain is used depending on the flavor goals of the distillery (and their price sensitivity since short-grain rice can sell for many times more than long-grain rice in Japan).

Sweet potatoes are added to the main fermentation. These potatoes are washed and trimmed before being either steamed or roasted before being added to the main fermentation. The skins are rarely removed as that is where much of the flavor lives. Steamed sweet potato-produced shochu represent a vast majority of the market.

With approximately 80 shochu distilleries in Kagoshima Prefecture (plus 28 in the Amami Islands making kokuto sugar shochu, but we will save that for the next episode) and another 40 or so distilleries in Miyazaki Prefecture, a huge majority of sweet potato shochu is made in Southern Kyushu.

Shochu made in Kagoshima from locally grown sweet potatoes qualifies for the WTO Geographic Indication of Satsuma Shochu, just as Kumamoto made rice shochu qualifies as Kuma Shochu and Iki Island made barley shochu can qualify as Iki Shochu.

Mentioned Sweet Potato Shochu Brands

IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ON THE SHOW

KURO KIRISHIMA, AKA KIRISHIMA

The black labeled Kuro Kirishima is by far the best-selling shochu in Japan. It’s made in Miyazaki Prefecture with black koji but is resolutely inoffensive. The red labeled Aka Kirishima is considered more premium and is often given as a gift. Made with red sweet potatoes.

SATSUMA SHIRANAMI

The OG in the minds of many Japanese people, Satsuma Shiranami was the first shochu brand to go national in the country. It has since been eclipsed by Kirishima. As you might have guessed by the name, this qualifies as Satsuma Shochu. The iconic wave label is instantly recognizable on bars throughout Japan.

YASUDA, FLAMINGO ORANGE

These new fruity styles have been gaining in popularity. Komasa has also been making these styles using different kinds of yeast.

Yasuda

Flamingo Orange

IKKOMON, BENIIKKO

The Ikkomon series is made with sweet potato koji. Tasting through these will give drinkers the sense of what the potato brings to the spirit without rice included. The blue and red labels are widely available in overseas markets. Sadly, the purple label is not.

THE HOZAN SERIES

An alternative tasting exploration is to try 3 different shochu made with 3 different koji types: black, white, and yellow. The Hozan Series helpfully color codes the labels. The yellow koji Tomi no Hozan is the best-selling yellow koji sweet potato shochu in Japan.

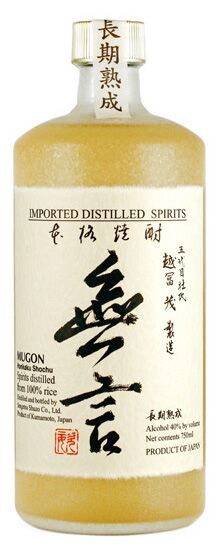

TENSHI NO YUWAKU

This barrel-aged full proof (40%) shochu is a beautiful spirit (in beautiful packaging) from Nishi Distillery, makers of the Hozan line. At 40% ABV this is higher than most sweet potato shochu, which usually starts life at 36-38% alcohol.

MAHOKO

Not aged in oak, but 16 years old at bottling, Mahoko is a handmade sweet potato shochu from Furusawa Distillery in Miyazaki. At 35% ABV it is only slightly diluted as the angel’s share has reduced the stored genshu to under 36% ABV. Newly available only in the U.S.

TOJI JUNPEI

Another handmade shochu from Miyazaki is Toji Junpei, made by a toji (master brewer-distiller) fittingly named Junpei. Available in the US market despite this being a tiny distillery.

YAMATO ZAKURA

Yamato Zakura is the smallest shochu distillery in Kagoshima and makes only white koji expressions. The main brand is the brand that Stephen helps make every fall.

ROKU DAIME YURI

The shochu Stephen was sipping on during the episode. Very hard to find anywhere in Japan. Made on Koshiki Island, home to only 2 distilleries. Won best of the best in a blind tasting in Dancyu Magazine, beating out all of the more famous brands.

MANZEN, MANZENAN, MANAZURU

Christopher was sipping on Manazuru during the show. These shochu are all made by Manzen Distillery. The main brand, Manzen, uses black koji while Manzenan uses yellow and Manazuru uses white. Manazuru is made just one time per year, so it is extremely hard to find leading Christopher to hunt it on auction all the time.

Rumor has it Christopher’s booze closet floor looks a little bit like this.

If we missed anything, please let us know, but this should keep you busy for a while.